Native-Art-in-Canada has affiliate relationships with some businesses and may receive a commission if readers choose to make a purchase.

- Home

- History of Native Art

Canadian Native Art

An Historical Overview

To understand Canadian native art ... or for that matter North American Indian art...it helps to have an appreciation of where it was fashioned, the lifestyle of its maker, the aesthetic values of the society and more than a smidgeon of information about the spiritual beliefs embedded in the culture.

In North America, examples of post-contact First Nations'

art have been collected, scrutinized and written about by explorers, fur

traders, Christian propagandists and anthropological researchers for

500 years.

If you live in the United States, don't be put off by the "Canadian" moniker....read what I have to say and then try mapping the information onto any section of the continent that most interests you.

The traditional imagery of the prehistoric and early post-contact periods was gradually influenced by European materials, techniques and motifs but it has always been a product of the culture which created it.

Yet from the earliest contact with Europeans to the present day, appreciation of the art has often been disconnected from the cultural character of the tribes in relation to where they lived, the manner in which they eked a living from the land, what they valued most, and how they viewed themselves in relationship to the rest of the universe.

That attitude has resulted in a distorted view of the immense depth, diversity and richness of Canadian native art history.

Six Regions of Canadian Native Art

Arctic Region

|

|

Necessarily self-sufficient because of their total isolation, people had managed to thrive in the Canadian Arctic for more than 5000 years before being 'discovered' by European adventurers. Their nomadic lifestyle dictated few possessions, other than those needed for survival, but the culture produced carvings of variable complexity that were manufactured from walrus ivory, bone, antler and very occasionally stone.

Some of the carvings were clearly made to be used, and some seem to have had a spiritual significance. But pendants or ornaments carved with complex geometric patterns, combs and tiny human figures would only have been made for pleasure. From the 1500's the Inuit residents of the area began trading with whalers and explorers who were looking for the Northwest Passage to India. As a result Inuit artisans started carving ivory miniatures as trade goods. A century later church missionaries even pushed for the production of Christian imagery! The nomadic lifestyle had collapsed by the 1940's and the Canadian Government looked for ideas that would provide a new income source for the Inuit hunters. By mid-century, James Houston, who wrote Eskimo Handicrafts, came up with the notion that the Inuit could be taught to make limited edition prints from images incised into slabs of soapstone. The government thought it was a great idea and funded artist cooperatives across the north. Contemporary Inuit art was born. |

Sub Arctic Region

|

|

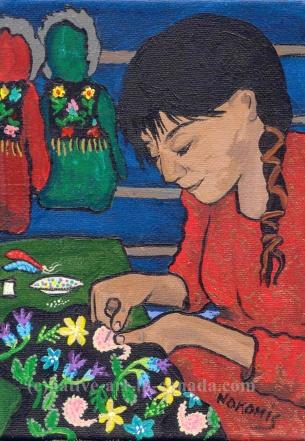

Native art from the Eastern Subartic is probably the oldest in Canada. The majority of prehistoric and early contact rock art sites are located in this region of the Canadian shield. The inhabitants - the Ojibwa, Cree, Algonquin, Ottawa, Montagnais, Naskapi, M'qMak and the Maliseet - lived a nomadic lifestyle based on hunting, fishing and the gathering of wild foods. All those cultures had somewhat similar spiritual beliefs and system of governance and their art reflected their environment. They decorated their clothing with self-styled beads made from bone and shells, coloured hides with plant based dyes, embellished their ceremonial headwear with feathers and fur and incised patterns into their birchbark baskets and canoes. For those people living north of the large cities, that lifestyle continued well into the 20th century but fabric and manufactured beads were used instead. That's my Mom sewing purchased beads onto black velveteen which would eventually become the yoke on a handmade coat. Even now...despite snowmobiles and aircraft...vestiges of the that way of life still exist. Native Art from the Western Subarctic was not quite as prolific. The Dene are linguistically distinct, have a different world view and a different system of governance. But environmental conditions were similar although the cold weather came earlier and stayed later. But their traditional crafts had much in common with their eastern neighbours. Decoration of personal gear and clothing was their major form of artistic expression. The artisans had a well developed sense of color and design. Caribou and moose hide was embellished with porcupine quills, beads and commercial threads in geometric and floral patterns. Years ago, I recall racing down the road from Yellowknife towards the MacKenzie River hoping that the ice bridge would still be open by the time I got there. Hoar frost covered the trees and because I hadn't seen another vehicle it seemed as if I was the only one living in that fantasy world. Suddenly...in the distance...I saw a figure dressed in scarlet come out of the bush, impale a branch into a snowbank and bend it towards the east. I knew what he was doing. He was a hunter who had made a kill and was marking the direction so that he and his friends could retrieve the carcass later. I pulled over to chat...strangers do that when they meet in the wilderness...and I was struck by the beauty of his clothing. This hunter's coat had been hand sewn from scarlet red duffel. The yoke was elaborately decorated with moose hide tufting, the hood embellished with fur from an arctic fox. His mukluks had been made from moose hide and were also tufted. I offered to give him a lift but he said that he'd pre-arranged for someone to pick him up somewhere along the highway before night set in. I complimented him on his beautiful clothes and he gave me a gentle smile. |

|

Moosehair tufting was introduced by the Grey nuns who moved into Fort Providence, Northwest Territories in the early 1900's. Above, a superior example of that craft decorates the moosehide gloves made by Bella Bonnetrouge of that community. I knew Bella. With children in tow and a rifle at hand, she tracked the moose, killed it, skinned and butchered it, dragged it home, shared the meat with friends and family, tanned the hide then smoked it with punky spruce wood ... (I can tell by the colour:) ... collected thousands of the white under-hairs that had grown along the spinal ridge on the moose' back, spent hours and hours sorting individual hairs into "shades of white" on a table beside a window so that when she dyed them each bundle was of a consistent colour, dried and packaged the coloured moose hairs into appropriately shaded bundles, trapped a beaver, shared the meat with family and friends, tanned its hide leaving the fur in place, used a home-made pattern to cut the glove sections to the exact size she wanted, tufted the appropriate sections of hide by sewing a multitude of dyed hair bundles ever so tightly together, 'carved' the moose hair into rounded tufts with nail scissors, sewed the sections together by hand, embellished the gloves with strips of beaver fur then sold or bartered them at the local store. Those particular gloves are now in a museum .... and are a fine example of how 'art' is produced by economic necessity. |

Southern Great Lakes Region

|

|

The southern Great Lakes, the St. Lawrence River valley and the boreal forest that extended south along the Atlantic seaboard and west to the headwaters of the Missouri River sourced the prehistoric Eastern Woodlands Indian art. But even in prehistoric times this culture was influenced by what was happening further afield. The Iroquois, for example, had established trade routes with the highly complex and economically advanced Eastern Woodland cultures along the Mississippi River. That culture had in turn been affected by Central American Mayan civilization. Technological innovations in pottery making came to Canada through that trade route. From the beginning of the historic period it was this area below the Great Lakes that suffered the most rapid cultural changes. Unlike their nomadic neighbours to the north, a milder climate had allowed many tribes to practice subsistence farming which meant that people lived in relatively permanent villages. The more sedentary lifestyle meant that their political and social institutions were different from their northern cousins and artisans had more time to advance artistic techniques. But by the 19th century many of the First Nations peoples living in this area had migrated both westward and eastward or in desperation were settling onto Reserves in the area. |

|

Art came to have a new purpose. It was a source of income to people whose traditional means of livelihood had been destroyed. Baskets, beaded necklaces, model birchbark canoes and even feathered headbands were made to be sold to outsiders...tourists and collectors of "native arts and crafts". |

Prairie Region

|

|

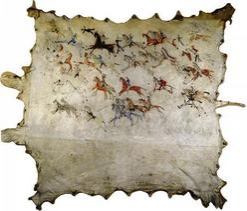

Historic prairie native art and culture, as it developed in the 19th century, was a combination of First Nations and mainstream cultures. It was the product of the increased mobility and effectiveness in the buffalo hunt that came with the introduction of horses and guns. Much of the art produced by the Bloods, the Blackfoot and the Assiniboine was similar in technique, to that of the subarctic and eastern neighbours and some of the materials used were the same. But most native art produced by people living on the prairies was two dimensional and painting on hides was the major genre. The Blackfoot lavishly painted the tipis of important men with naturalistic and geometric motifs. Large tipis might have used up to forty hides. Dream images on rawhide shields might be said to be comparable to contemporary surrealistic paintings in visionary and aesthetic impact. Painted buffalo robes were another major art form. Personal belongings like deer hide moccasins, jackets, dresses, leggings and shirts were embellished with porcupine quill work and beads. Rawhide containers of various sizes, parfleches for example, were unique to the area and each had its own distinct designs. |

Central Plateau of British Columbia

|

|

The Interior Salish ... the Lillooet, Thompson, Okanagan and Shuswap tribes ... lived in an area of Canada known nowadays as central British Columbia's plateau region. When easterly winds blow clouds from the Pacific they tend to bump into the mountains and drop their moisture before reaching the plateau. It's a dry climate, sparsely treed with many rocky outcroppings and in prehistoric times the residents created a large number of pictographs. on those same rocks. The Lillooet, Thompson, Okanagan and Shuswap of the historic era made finely crafted and watertight baskets using a coiling technique and decorated them with geometric motifs. The plateau peoples may have been the only First Nations group in Canada to have used textiles - they wove blankets from mountain goat hair - but next to nothing is known of their clothing or religious beliefs which would provide a context for an interpretation of their art. |

Northwest Coast Region

|

|

Northwest Coast Art is a term applied to a style of art that is produced by members of the various tribes that live on the west coast of Canada from the Vancouver area north to Alaska. This style of native art is distinguished by the use of form lines, and the use of characteristic oval, 'u' and 's' shaped forms. The imagery evolved from nature to include bears, ravens, eagles, and humans or legendary creatures such as thunderbirds. Before European contact the most common medium northwest coast artisans used was wood but contemporary artists use paper, canvas, glass, and precious metals. If paint is made part of the product the most common colours are red and black, but yellow is sometimes part of the design. |

Although the training, lifestyles and creative motivation of contemporary native artists differ profoundly from their ancient counterparts, today's Woodland art is actually sourced by traditional artistic representations used by prehistoric Eastern Woodland Indians.

Woodland School of Art and Cultural Survival

To understand the potential influence of contemporary Woodland

Art, it's worthwhile noting that long before Europeans arrived on the

shores of North America, First Nations people, for one reason or

another, faced cultural catastrophes and it was often artistic activity that rode to the rescue!

Norval Morrisseau is the grandfather of native art in Canada. His vision of himself and his people created the possibility that native culture and native artists could stand along side the art and culture of mainstream Canadian society.

The name given to the seven native artists who were members of the Indian Professional Artist's Association by Winnipeg Free Press reporter, Gary Scherbain.

The Grandmother of Canadian Native Art.

I was born in the bush north of Lake Superior when the spiritual traditions of the Anishinaabe were still practised and I paint memories of that time of my life.

As galleries and museums began to rethink the definition of First Nation's art more and more native artists saw career possibilities. Here's a small sampling of contemporary native artists listed alphabetically. Not all would be considered woodland artists, some like Allen Sapp and Gerald Tailfeathers developed their careers independently.